Going underground

The London Underground tube map is a master class in information visualization. It's been described in detail in many, many places, so I'm just going to give you a summary of why it's so special and what we can learn from it. Some of the lessons are about good visual design principles, some are about the limitations of design, and some of them are about wealth and poverty and the unintended consequences of abstraction.

(London Underground map.)

The problem

From its start in 1863, the underground train system in London grew in a haphazard fashion. With different railway companies building different lines there was no sense of creating a coherent system.

Despite the disorder, when it was first built it was viewed as a marvel and had a cultural impact beyond just transport; Conan Doyle wove it into Sherlock Holmes stories, H.G. Wells created science fiction involving it, and Virginia Woolf and others wrote about it too.

After various financial problems, the system was unified under government control. The government authority running it wanted to promote its use to reduce street-level congestion but the problem was, there were many different lines that only served part of the capital. Making it easy to use the system was hard.

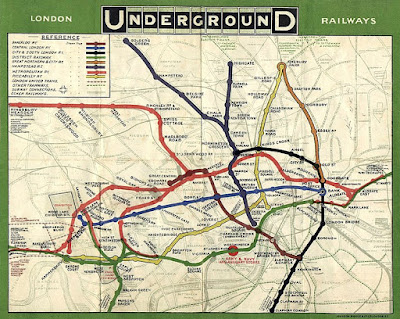

Here's an early map of the system so you can see the problem.

(1908 tube map. Image source: Wikimedia Commons.)

The map's hard to read and it's hard to follow. It's visually very cluttered and there are lots of distracting details; it's not clear why some things are marked on the map at all (why is ARMY & NAVY AND AUXILLARY STORES marked so prominently?). The font is hard to read, the text orientation is inconsistent, and the contrast of station names with the background isn't high enough.

The problem gets even worse when you zoom out to look at the entire system. Bear in mind, stations in central London are close together but they get further apart as you go into the suburbs. Here's an early map of the entire system, do you think you could navigate it?

(1931 whole system tube map.)

Of course, the printing technology of the time was more limited than it is now, which made information representation harder.

Design ideas in culture

To understand how the tube map as we know it was created, we have to understand a little of the design culture of the time (the early 1930s).

Electrical engineering was starting as a discipline and engineers were creating circuit diagrams for new electrical devices. These circuit diagrams showed the connection between electrical components, not how they were laid out on a circuit board. Circuit diagrams are examples of topological maps.

The Bauhaus school in Germany was emphasizing art and design in mass-produced items, bringing high-quality design aesthetics into everyday goods. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, the last director of the Bauhaus school, used a key aphorism that summarized much of their design philosophy: "less is more".

(Bauhaus kitchen design 1928 - they invented much of the modern design world. Image source: Wikimedia Commons, License: Public domain)

The modern art movement was in full swing, with the principles of abstraction coming very much to the fore. Artists were abstracting from reality in an attempt to represent an underlying truth about their subjects or about the world.

(Piet Mondrian, Composition 10. Image source: Wikimedia Commons, License: Public Domain.)

To put it simply, the early 1930s were a heyday of design that created much of our modern visual design language.

Harry Beck's solution - form follows function

In 1931, Harry Beck, a draughtsman for London Underground, proposed a new underground map. Beck's map was clearly based on circuit diagrams: it removed unnecessary detail to focus on what was needed. In Beck's view, what was necessary for the tube map was just the stations and the lines, plus a single underlying geographical detail, the river Thames.

Here's his original map. There's a lot here that's very, very different from the early geographical maps.

The design grammar of the tube map

The modern tube map is a much more complex beast, but it still retains the ideas Harry Beck created. For simplicity, I'm going to use the modern tube map to explain Beck's design innovations. There is one underlying and unifying idea behind everything I'm going to describe: consistency.

Topological not geographical. This is the key abstraction and it was key to the success of Beck's original map. On the ground, tube lines snake around and follow paths determined by geography and the urban landscape. This makes the relationship between tube lines confusing. Beck redrew the tube lines as straight lines without attempting to preserve the geographic relations of tube lines to one another. He made the stations more or less equidistant from each other, whereas, on the ground, the distance between stations varies widely.

The two images below show the tube map and a geographical representation of the same map. Note how the tube map substantially distorts the underlying geography.

Removal of almost all underlying geographical features. The only geographical feature on tube maps is the river Thames. Some versions of the tube map removed it, but the public wanted it put back in, so it's been a consistent feature for years now.

(The river Thames, in blue, is the only geographic feature on the map.)

A single consistent font. Station names are written with the same orientation. Using the same font and the same text orientation makes reading the map easier. The tube has its own font, New Johnston, to give a sense of corporate identity.

(Same text orientation, same font everywhere.)

High contrast. This is something that's become easier with modern printing technology and good-quality white paper. But there are problems. The tube uses a system of fare zones which are often added to the map (you can see them in the first two maps in this section, they're the gray and white bands). Although this is important information if you're paying for your tube ticket, it does add visual clutter. Because of the number of stations on the system, many modern maps add a grid so you can locate stations. Gridlines are another cluttering feature.

Consistent symbols. The map uses a small set of symbols consistently. The symbol for a station is a 'tick' (for example, Goodge Street or Russell Square). The symbol for a station that connects two or more lines is a circle (for example, Warren Street or Holborn).

Graphical rules. Angles and curves are consistent throughout the map, with few exceptions - clearly, the map was constructed using a consistent set of layout rules. For example, tube lines are shown as horizontal, vertical, or 45-degree lines in almost all cases.

The challenge for the future

The demand for mass transit in London has been growing for very many years which means London Underground is likely to have more development over time (new lines, new stations). This poses challenges for map makers.

The latest underground maps are much more complicated than Harry Beck's original. Newer maps incorporate the south London tram system, some overground trains, and of course the new Elizabeth Line. At some point, a system becomes so complex that even an abstract simplification becomes too complex. Perhaps we'll need a map for the map.

A trap for the unwary

The tube map is topological, not geographical. On the map, tube stations are roughly the same distance apart, something that's very much not the case on the ground.

Let's imagine you had to go from Warren Street to Great Portland Street. How would you do it? Maybe you would get the Victoria Line southbound to Oxford Circus, change to the Bakerloo Line northbound, change again at Baker Street, and get the Circle Line eastbound to Great Portland Street. That's a lot of changes and trains. Why not just walk from Warren Street to Great Portland Street? They're less than 500m apart and you can do the walk in under 5 minutes. The tube map misleads people into doing stuff like this all the time.

Let's imagine it's a lovely spring day and you're traveling to Chesham on the Metropolitan Line. If Great Portland Street and Warren Street are only 482m apart, then it must be a nice walk between Chalfont & Latimer and Chesham, especially as they're out in the leafy suburbs. Is this a good idea? Maybe not. These stations are 6.19km apart.

Abstractions are great, but you need to understand that's exactly what they are and how they can mislead you.

Using the map to represent data

The tube map is an icon, not just of the tube system, but of London itself. Because of its iconic status, researchers have used it as a vehicle to represent different data about the city.

James Cheshire of University College London mapped life expectancy data to tube stations, the idea being, you can spot health disparities between different parts of the city. He produced a great map you can visit at tubecreature.com. Here's a screenshot of part of his map.

You go from a life expectancy of 78 at Stockwell to 89 at Green Park, but the two stations are just 4 stops apart. His map shows how disparities occur across very short distances.

Mark Green of the University of Sheffield had a similar idea, but this time using a more generic deprivation score. Here's his take on deprivation and the tube map, the bigger circles representing higher deprivation.

Once again, we see the same thing, big differences in deprivation over short distances.

What the tube map hides

Let me show you a geographical layout of the modern tube system courtesy of Wikimedia. Do you spot what's odd about it?

(Geographical arrangement of tube lines. Image source: Wikimedia Commons, License: Creative Commons.)

Look at the tube system in southeast London. What tube system? There are no tube trains in southeast London. North London has lots of tube trains, southwest London has some, and southeast London has none at all. What part of London do you think is the poorest?

The tube map was never designed to indicate wealth and poverty, but it does that. It clearly shows which parts of London were wealthy enough to warrant underground construction and which were not. Of course, not every area in London has a tube station, even outside the southeast of London. Cricklewood (population 80,000) in northwest London doesn't have a tube station and is nowhere to be seen on the tube map.

The tube map leaves off underserved areas entirely, it's as if southeast London (and Cricklewood and other places) don't exist. An abstraction meant to aid the user makes whole communities invisible.

Now look back at the previous section and the use of the tube map to indicate poverty and inequality in London. If the tube map is an iconic representation of London, what does that say about the areas that aren't even on the map? Perhaps it's a case of 'out of sight, out of mind'.

This is a clear reminder that information design is a deeply human endeavor. A value-neutral expression of information doesn't exist, and maybe we shouldn't expect it to.

Takeaways for the data scientist

As data scientists, we have to visualize data, not just for our fellow data scientists, but more importantly for the businesses we serve. We have to make it easy to understand and easy to interpret data. The London Underground tube map shows how ideas from outside science (circuit diagrams, Bauhaus, modernism) can help; information representation is, after all, a human endeavor. But the map shows the limits to abstraction and how we can be unintentionally led astray.

The map also shows the hidden effects of wealth inequality and the power of exclusion; what we do does not exist in a cultural vacuum, which is true for both the tube map and the charts we produce too.